Kate had no desire to move to Toronto. None whatsoever. Yet that seemed to be the only option if she was going to pursue her dreams of going into forensic anthropology. She tried to do the next best thing while staying in Montreal. Kate applied to do a Bachelor of Arts and Science at McGill, and was accepted. She chose the disciplines of anthropology and biomedical sciences, thinking that what she learned could later be applied to getting a Masters in forensic anthropology. But alas, the program was not for her. Kate could not stand her molecular biology class. She didn’t understand what was going on, nor did she care to learn it—a dangerous combination. She eventually withdrew from the course, realizing that she hated it so much that she could never do well. Kate loved her physiology and anatomy classes, especially the anatomy class. But anatomy was not offered as a program at McGill. In the end, Kate opted to pursue only a Bachelor of Arts, and keep anthropology as her major. She loved all of her archaeology classes.

*****

When she learned that she had to pick up a minor, Kate was stumped. She didn’t know what interested her! Between the courses she had taken, she already had two earth and planetary science classes, so she decided to go for it. It turns out it was a good choice for Kate. Geology classes involved a lot about ancient times, about the earth. She learned about invertebrate palaeontology, and how to classify beautiful shiny minerals. Kate was a natural at geology, and it actually fit in quite nicely with her archaeology classes.

Kate started and finished her minor in one year, culminating with a field school that she did not have the pre-requisites for. She gained permission from the teacher, and loved every moment of it. The field trip had crews of geologists wandering and mapping the structural geology of Sutton. Kate thoroughly enjoyed searching out traces of geology under fallen trees and measuring the sides of cliffs. She loved hiking through the woods for long, eight hour days and covering the area. She loved searching for dolomite, an important transition stage for the geology of the region that would help tremendously with the mapping. Finding the dolomite was the best part, as it involved following her nose. Kate could literally sniff out dolomite. Because of the specific chemistry of the mineral, wild garlic selectively grew on dolomite outcrops. The sweet smell of wild garlic was a cross between regular garlic and onions, and it made Kate’s mouth water. She especially liked looking for dolomite.

Kate did consider taking on geology as a second minor, but she could not see herself continuing on and making it her career. The geologist’s best friend was his dog, as life was spent moving around and traipsing, solo, through the backcountry scoping out geological features. Most geologists ended up employed by oil companies as prospectors. This was not the life for Kate.

*****

Before that field school—immediately before—Kate bought her first car. The Jackal, her ’94 Civic, waited for her at home at the end of that field school.

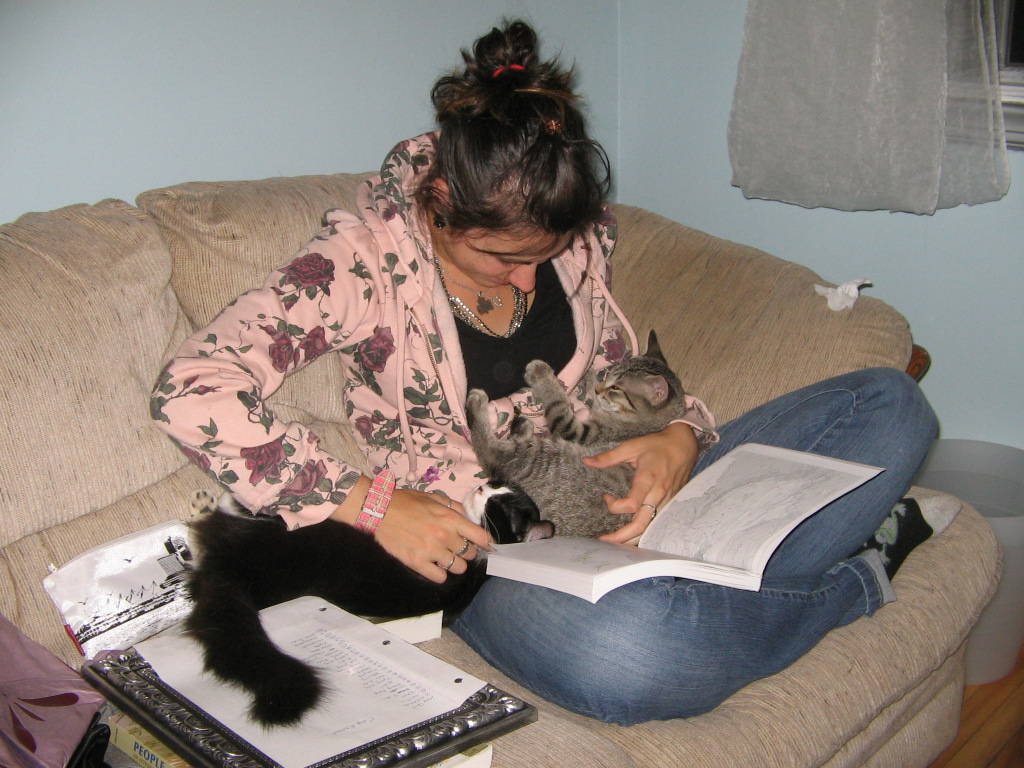

The next summer, in 2007, Kate moved out of her parents house and in to her apartment with Jordan. At 21, Kate wanted to independence that came with living on her own. Moving was a very stressful time, but she was soon settled into her new place. Once she got her kitties, Floyd and Scooty, it really became a home.

*****

The next year, Kate finally got her hands dirty as an archaeologist. VERY dirty. The team of archaeologists was recruited by Park Safari. Park Safari had no records of where their animals were buried prior to the early 2000s. They knew that they had an elephant and a rhinoceros that had died, and they wanted the skeletons to assemble and put on display. Not knowing where to look, they got archaeologists on board to help them find the skeletons. The field course took place every second Friday for the entire semester. First, they searched for the rhino. Kate ended up on what was officially termed “Team Loser”, because all they seemed to find were rocks!

Another team was more successful in their test pit, so the whole team was called over to widen the excavation area. They knew they were successful for a few reasons. The soil in this test pit was darker and clearly richer—as though it contained the materials from a decomposing body. Again, though, it was following her nose that led Kate to believe that they had found the rhinoceros. There was a putrid smell, almost overwhelming, that spilled out of the pit. It was like a pile of compost in the hot summer sun with hints of chicken that had been sitting out for too long. It was vile, and it was all Kate could do not to gag. Really, though, that was not about to keep her from playing in the pit!

The further they dug, the more certain they were that they had found the right place! A bone was uncovered—a lone spike exposed in the center of the pit. The soil immediately touching this spike was darker than the rest. They continued on. Kate, slowly working away with her trowel, eventually exposed a layer of soil that was white and texturally very different from the surrounding soil. She called her professor over.

“André, look at this” she said. He glanced at it, and said something along the lines of interesting, keep going. So she did. Kate continued and exposed an area of about 15cm by 15cm of this white layer. She poked it with her trowel, and it bounced back. André happened to be watching. He laughed.

“André”, Kate said, “Soil does not bounce back when you poke it”. And this is where her anatomy classes, where she had studied real dissected bodies, came in handy.

“This is not soil. This is fat. This is a huge layer of fat. This rhinoceros is not ready to come out of the ground” she stated matter-of-factly. Of course, André had already come to this conclusion. His experience likely told him as soon as they experienced the stench and the colour of the soil that they would not be excavating a skeleton here, at least not without haz-mat suits. But André had wanted the budding archaeologists to find that out on their own.

So the team moved on, in the following weeks, to look for the elephant. It had been buried for at least ten years, when the rhinoceros had only been buried for about five—the Park Safari records showed that much. They crossed the street to where the elephant was supposed to be buried, and began anew with their test pits. This is where team loser met their first success! Kate herself stuck a shovel into the soil, flipped a layer of grass, and was immediately greeted by a macaque mandible! It was very exciting, her first find! She labelled it and bagged it, but did not uncover any more of that monkey’s remains.

Like a replay of the rhinoceros, one of the pits began to emit that same rank smell of decaying fat. Deeper the pit was dug, and the team was certain that they had uncovered the elephant. The 1m by 1m test pit was expanded to be dug deeper, to eventually expose, across the entire bottom of the pit, the same white, bouncy layer of subcutaneous fat. The elephant would not be uncovered either!

They had new hope, though. A horn had been uncovered in a pit that did not smell so foul. The team carried on with that pit, and ended up unearthing ancient evils. It turned out that what looked like some sort of demon was actually and watusi, a breed of African cattle.

The idealistic conception of the archaeologist sitting in dry soil, using a brush to brush away loose powdery layers of dirt, it turns out, could not have been further from the reality of digging at Park Safari. The earth was very wet. There seemed to be an underground spring, as they perpetually had to bail water out of the watusi pit. Each week when they returned, the pit was full to the brim with water, topped by the oily slick produced by decomposing flesh. They would form a line and bail with buckets, but the earth within the pit was wet, muddy, and squelchy. It would suck rubber boots right into it, and more than once Kate’s boots let mud in from the top. Brushes would not have helped here; water had to be used to wash the wet mud from the bones as they were exposed. The entire skeleton was eventually unearthed, almost fully decomposed. The one remaining reminder that the watusi had been buried, flesh and blood, was the sac of stomach contents—still located where the watusi’s stomach would have been—that had yet to decompose. What was left was the texture and colour of cream cheese—but it smelled nothing like cream cheese. It smelled like a swamp in the springtime and rotting flesh all at the same time. But the archaeologists were all used to this by now, so of course they all got their trowels in there to play with it! Kate did poke it, of course, but did not eat cream cheese for a few months thereafter!

Eventually, the ground froze and the archaeologists were stopped in their tracks but the impending winter. They marked the site so no one would fall into the pit over the winter, and left.

Read more about the dig at: http://mcgillzooarchaeology.blogspot.com/2007_09_01_archive.html

*****

That winter, Kate took an extension of that field course: she was on the team that would help clean the bones and assemble them so that they could be displayed at Park Safari. This was a long process. Kate bleached and drilled, epoxied and moulded, sculpted and suspended. It was a complicated procedure, because no one—including the very pregnant instructor—had ever done anything like assembling a watusi before! If the smell of decomposing flesh at Park Safari was bad, the team encountered a smell that was even worse. First off, they learned that drilling through vertebrae was nearly impossible. It took a significant amount of force, and many broken drill bits. They learned that they needed to start with a small drill bit, and work their way up to a large one. But the smell once they broke through into each vertebra was the worst smell Kate had yet experienced. Not only did it smell like decomposing fats—the marrow inside which was still in the process of decomposing—but it smelled like burning rotting marrow because of the heat that the drill produced while working its way through the bone. It got hot enough that it would smoke, and the smoke caused the stench to permeate throughout the lab.

Eventually, the watusi came together, and Kate was proud to be a part of it, and glad that she could continue her dreams of working with bones.

*****

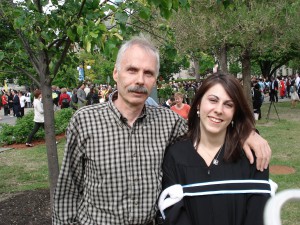

That field experience brought Kate to the end of her undergraduate degree. She

graduated in the spring of 2008, with Great Distinction and on the Dean’s List. Where to next?